[ad_1]

Discover

This text initially appeared in Knowable Journal.

Evolutionary geneticist and choral singer Jenny Graves has carried out Joseph Haydn’s masterpiece, The Creation, on many events. The well-known oratorio chronicles the seven days of biblical creation as described within the E book of Genesis. But Graves, who has spent the previous 60 years finding out the wonders of evolution, grew bored with singing about Adam and Eve. So she penned a secular retelling of our origin story—drawing from scientific discoveries in cosmology, molecular biology, evolutionary genetics, ecology, and anthropology—and teamed up with a poet and a composer to carry the 110-minute choral work to fruition.

The piece, Origins of the Universe, of Life, of Species, of Humanity, is daring, compelling, and humorous, very similar to Graves. One in every of its most provocative verses, “No cosmic hand guides variety,” comes early within the seventh motion. A chorister protested, suggesting she revise the wording to be extra allegorical or imprecise. “I don’t need it to be imprecise,” Graves recollects saying. “I would like the origin from science—and science is what I’m going to make use of.” One tenor left throughout rehearsals, telling Graves they couldn’t sing one thing they didn’t imagine in. She smiled her disarming smile and responded, “Oh, why not? We do this on a regular basis. Do you imagine in Santa Claus?”

Most individuals embraced Graves’s imaginative and prescient, and final summer time, she acquired a standing ovation after performing Origins alongside a 100-voice choir, full orchestra, and 4 soloists at a glittering live performance corridor in Melbourne, Australia. Biologist Harris Lewin, who has identified Graves for the reason that Nineties, says he was blown away by Graves’s newest achievement.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

“She’s completely sensible. She’s artistic. She’s unique,” he says. “There’s nobody else like Jenny.”

Impressed by a Budgerigar

Graves was born in Adelaide, South Australia, a metropolis identified for its vibrant cultural scene and parklands brimming with wildlife. Each her dad and mom had been scientists: her father a soil physicist and her mom a geography lecturer. However as a baby, she didn’t really feel a selected pull towards science. She appreciated studying, writing, and artwork. When she first took biology, she hated the topic—it appeared like a bunch of info with no rhyme or purpose.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

Then, someday, her highschool trainer gave a lesson on genetics, utilizing the budgerigar (also referred to as the frequent parakeet) for example. The trainer defined that while you crossed the blue budgerigar with the yellow budgerigar, all of the offspring had been inexperienced; while you crossed the inexperienced budgerigars with one another, 1 / 4 of the progeny had been blue, half had been inexperienced, and 1 / 4 had been yellow. All of the sudden, all of it made sense. “Wow, there are guidelines; there are guidelines, in spite of everything,” says Graves. “After all, I didn’t uncover the true guidelines of biology, that are evolutionary guidelines, and I found that a lot, a lot later.”

One tenor left throughout rehearsals, telling Graves they couldn’t sing one thing they didn’t imagine in.

Graves studied genetics on the College of Adelaide, conducting undergraduate analysis on sex-determining chromosomes in kangaroos. She received a Fulbright grant to get her Ph.D. at Berkeley. It was the Sixties, the last decade of peace, love, and music. Anti-war protests had been a fixture on campus. Graves met her husband whereas enjoying star-crossed lovers in a musical dubbed NucleoSide Story, a riff on West Aspect Story, in regards to the warring departments of molecular biology and biochemistry. He later inspired her to affix a choir with him; the couple, who’ve two daughters and three grandchildren, have been making music collectively ever since.

At Berkeley, Graves designed difficult experiments that pressured mouse, hamster, and human cells to fuse collectively in petri dishes. When she moved again to Australia as a lecturer at La Trobe College in Melbourne, a colleague prompt she use her cell hybrids to map genes in Australian mammals. Initially, she was hesitant to review the native natural world, frightened that it’d restrict the influence of her work. However she finally realized she may glean lots of info by evaluating the genomes of distantly associated animals.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

“I obtained completely transfixed,” she stated. “It’s form of like a large jigsaw puzzle.” It was the early days of gene mapping, and scientists knew little in regards to the mammalian genome. “We solely had 16 genes mapped in people and never a single one in kangaroos. And so folks had puzzled, how conserved is our genome?”

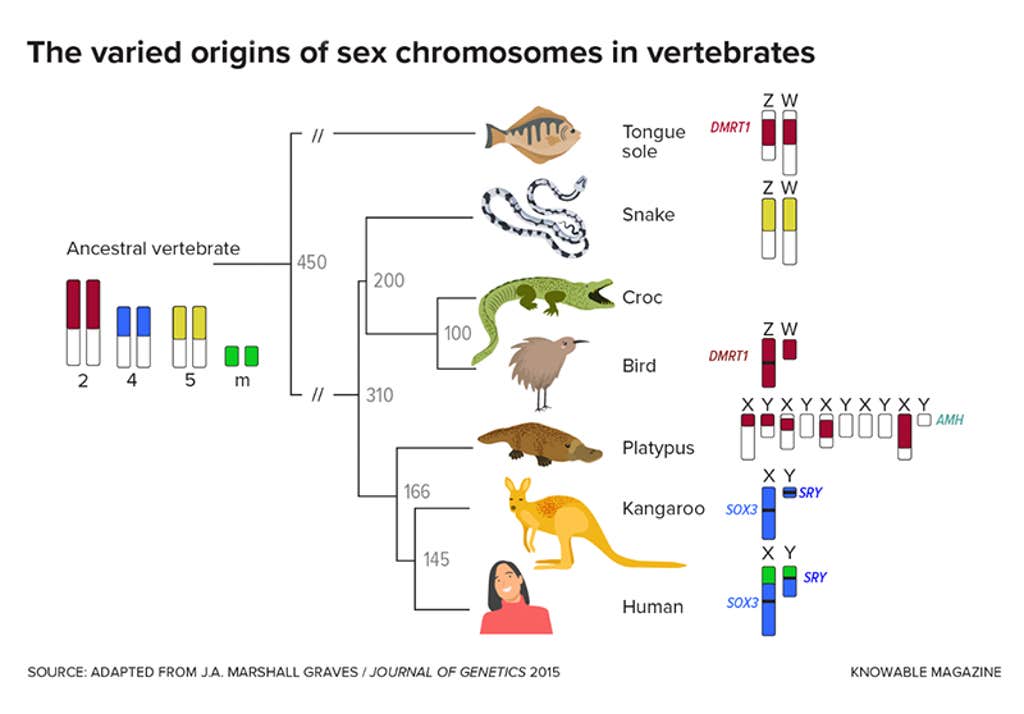

Extremely conserved genes are comparable throughout totally different species and have been maintained over hundreds of thousands of years of evolution. These genes sometimes stick round as a result of they serve an important operate, similar to in replica or metabolism. In addition they function signposts for scientists making an attempt to decipher how the genome is organized and the way it has modified as numerous species have developed. Within the late Nineteen Eighties and early Nineties, Graves was a part of a cadre of scientists who started evaluating genes and chromosomes from a menagerie of creatures, together with kangaroos, platypuses, cats, cows, pigs, monkeys, birds, and, in fact, mice and people, laying the inspiration for a area of research that might later be often called comparative genomics.

Utilizing this comparative strategy, Graves challenged a textbook paradigm often called Ohno’s regulation. Proposed by the biologist Susumu Ohno, the regulation acknowledged that the X chromosome (one of many chromosomes concerned in dictating an animal’s intercourse) carried the identical genes in all mammalian species. However Graves confirmed that genes on the quick arm of the X chromosome in people mapped to a unique chromosome in kangaroos. In a profession retrospective within the Annual Assessment of Animal Biosciences, she recollects visiting Ohno at his workplace on the Metropolis of Hope most cancers middle within the better Los Angeles space, and sharing the information. He didn’t appear to care that her marsupials had damaged his regulation. As an alternative, he led her to his laptop to point out off his newest challenge: turning DNA sequences into musical items.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

The Unbelievable Shrinking Y

Graves’s curiosity in intercourse chromosomes intensified after she obtained caught up within the race to find the gene on the Y chromosome that determines the event of male sexual traits. Geneticist David Web page thought he had discovered the testis-determining gene, which he known as ZFY, and reached out to Graves to verify his discovery in kangaroos. As an alternative, her scholar Andrew Sinclair confirmed that ZFY was the flawed gene. “It was on chromosome 5, which is a wierd place for a intercourse gene,” says Graves. Sinclair went on to discover the true sex-determining area on the Y chromosome, and aptly named it SRY.

Then, in 1992, Graves skilled a major setback: a near-fatal cerebral hemorrhage adopted by 18 months in rehabilitation. Graves was unable to learn or stroll at first. However she may suppose and sort, so she wrote 5 grant proposals. All of them obtained funded.

“She was resilient,” says Rachel O’Neill, who joined the Graves lab as a Ph.D. scholar round that point. O’Neill wasn’t conscious of her boss’ well being points till a lot later. However she remembers watching as Graves furiously wrote grants, all whereas preventing for entry to the identical lab house and sources afforded to her male colleagues. “We talked in regards to the dynamics of being one of many few ladies within the area in Australia, and the way straightforward it was for folks to dismiss what she stated,” O’Neill recollects. “She had a expertise for letting it simply wash off her.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

When O’Neill acquired her first manuscript rejection, she sought recommendation from Graves, who informed her that each manuscript was a battle and that she simply needed to preserve preventing. Graves pulled out her first rejection letter, through which the reviewer had principally written, O’Neill recollects, “I didn’t prefer it, and my pals didn’t both.” Graves informed O’Neill that’s what all rejections say, and if she may persuade the naysayers to love her work, she may do something. O’Neill stated she nonetheless shares that story along with her college students on the College of Connecticut, the place she is a molecular biologist. And he or she thinks of it each time she will get a very nasty assessment.

Over time, Graves grew adept at profitable over salty scientists and uninterested undergrads alike. As a trainer, she usually turned to her love of music to get her level throughout, writing songs about genetics to brighten up her lectures. “They had been so amazed—in a boring summer time class I’d instantly sing The Mutant’s Lament or Love’s a Plasmid,” she says. “I run into my previous college students everywhere in the world—in airports in France and that form of factor—and they’ll say, ‘I’ll always remember your second-year lectures!’”

Graves usually turned to music to get her level throughout, writing songs about genetics to brighten up her lectures.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

In 1999, Graves was elected to the Australian Academy of Science. Shortly after, she took a analysis place on the Australian Nationwide College in Canberra, the place she based the comparative genomics division. There, she infamously predicted that the human Y chromosome was shrinking and would disappear in about 4 million to five million years. The prediction raised a furor as folks fretted in regards to the destiny of our species. “We haven’t been by means of 1 million years—we expect we’re frightened in regards to the Y chromosome in 4 million years?” she recollects. “I assumed that was extraordinarily humorous.”

“She’s a provocateur,” says Lewin, “and he or she relishes being in a spot that may get folks to suppose. By saying the Y will disappear, OK, that will get lots of consideration. What it does is, it attracts you to the precise science that she and others working within the house are doing.”

Graves has generated scads of thought-provoking findings. She confirmed that prime temperatures can reverse the intercourse of the bearded dragon, and that the platypus has 10 intercourse chromosomes unrelated to the XY system of different mammals. Her analysis has yielded vital insights into the evolution of genes and chromosomes throughout all animal species, together with people. Finally, she was named a Thinker-in-Residence on the College of Canberra, giving her extra freedom to deal with large concepts.

A “Preposterous Concept“

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

In 2016, Lewin invited Graves to the Wellcome Belief in London to talk on the official launch of the Earth BioGenome Venture, an bold effort to sequence all 1.8 million identified species of crops, animals, fungi, and different eukaryotic life on the planet. Lewin says her discuss helped to catalyze the multibillion-dollar challenge in methods few others may.

Graves picked examples from totally different branches of the tree of life, describing sudden discoveries which have formed the understanding of biology. How the single-celled Tetrahymena was used to find telomerase, an enzyme concerned in growing older and most cancers. How arrow-shaped flatworms often called planarians can regenerate after being chopped into items, informing analysis on stem cells and therapeutic. Graves argued that if such information could possibly be gleaned from only a few species, think about what might be realized from sequencing all the things else.

“She’s a very nice speaker and performer,” says O’Neill, one of many 1000’s of scientists who joined the challenge. “When she speaks, everybody within the room listens.”

In recent times, Graves has taken her act to a brand new degree. She acknowledged that making a science-based sequel to Haydn’s The Creation was a “preposterous concept.” However when she lastly sat all the way down to do it, she wrote the entire thing from begin to end in every week and a half. Poet and fellow chorister Leigh Hay helped edit the phrases, and composer Nicholas Buc put them to music.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

“I believe science could be very stunning,” says Graves. “Simply have a look at the James Webb telescope photos: Stunning science is true there. Look down on the microscope: stunning science. The concept of expressing stunning science and delightful music all the time actually appealed to me.”

Graves’s Origins portrays not simply the great thing about science but additionally its ugly facet. It spans the Massive Bang to the sixth mass extinction, vividly describing the molecular underpinnings of life and the uniquely human endeavor to grasp it. One of the vital in style moments provides Rosalind Franklin due credit score for her function within the discovery of the DNA double helix, which earned the “antiheroes,” James Watson and Francis Crick, a shared Nobel Prize.

Given the selection, Graves desires Origins to be her legacy. She would love for folks to take heed to her sweeping science oratorio 100 years from now.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

“Science is a really artistic self-discipline; it requires you to suppose creatively to outwit nature and discover out the secrets and techniques. However it is rather totally different creating one thing like Origins,” she says.

“A few of my stunning outcomes turned out to be actually vital—I really like them, they’re terrific, and I believe they’re artistic—but when I hadn’t achieved them, another person would have. But when I hadn’t written Origins, no person else would have.”

This text initially appeared in Knowable Journal, a nonprofit publication devoted to creating scientific information accessible to all. Join Knowable Journal’s e-newsletter.

Lead picture: Australian researcher Jennifer Ann Marshall Graves has melded her ardour for music and science in an bold choral work. Credit score: Knowable Journal.

ADVERTISEMENT

Log in

or

Be a part of now

.

[ad_2]

Supply hyperlink