[ad_1]

Explore

Philosopher of science Peter Godfrey-Smith has spent decades considering the mental life of animals. His ongoing work on octopus cognition has helped to frame the discussion about how we might think about intelligences other than our own.

His recent books, Other Minds: The Octopus, the Sea, and the Deep Origins of Consciousness and Metazoa: Animal Life and the Birth of the Mindexplore the evolution of animal sentience, felt experience, and intelligence. His new book, Living on Earth: Forests, Consciousness, and the Making of the Worldcompletes this trilogy. It explores not just how minds evolved on Earth, but how minds have shaped the evolution of life on Earth. His bold thesis envisions organisms as causes, rather than as simply a result of millions of years of natural selection and evolution.

I recently caught up with Godfrey-Smith, who is a professor at the University of Sydney, over video. Our conversations range over the origins of life, how movement might have led to consciousness, and how language is just “kind of a weird thing that happened in our minds.”

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

You write, “The history of life is not just a series of new creatures appearing on the stage; the new arrivals change the stage itself.” What are some of your favorite examples?

The creation of the oxygen-rich atmosphere by cyanobacteria. Cyanobacteria get incorporated into other organisms like algae, and then green algae evolve into land plants and carpet the Earth in these solar panels that continue to condition the atmosphere. That was way back before there was anything that could reasonably be called consciousness, and also at a stage when the big effects that the organisms were having were in a fortuitous sense, because it wasn't to the cyanobacteria's advantage to fill the atmosphere with oxygen . It was kind of a byproduct.

Then there's the huge current example, which is us and our effects on climate, on wild natural populations, and on the whole biomass of the world through agriculture.

Then we have important intermediate cases. I would emphasize the effects that land plants, especially flowering plants, have. They shape rivers, which then shape the landscape. They turn rivers into more directed, coherent flows of water through their root systems. Through the action of their roots and chemicals, they change the weathering cycles through which carbon and oxygen have this very important and rather complicated dance on different time scales. There's the faster carbon cycle involving photosynthesis and respiration, and there's a slow one involving the weathering of rocks and the laying down of new rocks in the oceans.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

If life shapes the Earth—not just chemically, but also through action and behaviors, which are the product of mind—how might we know what it's like to inhabit the mind of a bee or an animal that's making behavioral choices?

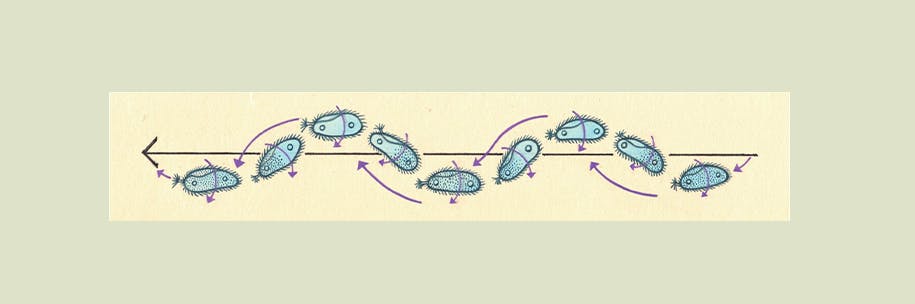

It's a history of choice that starts at a stage when the word “choice” has to be used cautiously, because there's a sense in which bacteria make choices, and other microorganisms and organisms without a nervous system. There's a directedness of their activities.

One of the things you then get as a consequence of co-evolutionary processes, the attempts to make life work with particular animals, is that choices become more refined. They become based in nervous systems. They become genuine mental choices.

So choice and mentality are embedded within living activity, but through the history of life, especially animal life, it's become more conscious, more deliberate, more intentional. One example I like to emphasize is the transition from purely habit-based forms of choice to plan-based, or foresight-based forms of choice. That's a situation where animals become not only able to produce actions because of their good consequences, but they can also represent those consequences and do novel actions because of their likely good consequences. That human, reflective, social choice, where we talk about what to do, reflect on the consequences, that's kind of the endpoint for now.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

There's a sense in which bacteria make choices.

How due the choices evolve over time to be more deliberate?

One way to put it would be to say, the early books talked about the origin of felt experience, how this weird feature of the living world came to exist. And in the third book, the presence of felt experience, felt evaluation, self-conscious reflection, becomes part of the history of choice.

How does the evolution of consciousness look, from my point of view? I think of it as, to some extent, a not-inevitable, but natural consequence of the animal way of being. You've got animals like sponges and anemones that are very limited in their actions, but for the most part, animals make a living by acting, by behaving, by controlling the motion of their parts. Controlled motion is this animal specialty, through muscle, through nervous systems.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

The evolution of action yields the evolution of subjectivity, of the formation of a point of view—action is done from a point of view. Points of view are the origins of action. And an animal is a kind of nexus where information's coming in from various sources, forming, well, something! It might be just habits. It might be intentions. It might be conscious, reflective, thought. Whatever it is in there, it's the basis of action from the point of view of that particular organism.

So we have animals evolving a point of view and making choices, often in the context of social groups—some perhaps even within a culture. And then we arrive at … language?

Roughly speaking, there are two camps on the origins of language. There's the kind of cultural camp where you have lots of lots and lots of communicatively reinforced behaviors. Possibly gesture was the beginning of sophistication here, rather than vocalization. And vocalization came along later, and the whole thing becomes more complicated over time.

Then there is the picture in much 20th-century linguistics, which were somewhat different. It was the idea that the origins of language lie more in a kind of a weird thing that happened in our minds, in the brain. It's not so much a social thing, and its origin is that our brains just became different and language was an outgrowth or an expression of this basic rewiring of parts of our brains. This is the Noam Chomsky program.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

There's still these two views. I'm more on the second side.

Writing has a very different origin. It's a late comer. It's only about 5,000 years old. It's natural to think, oh yeah, once you're talking, it would make perfect sense to then encode permanently through inscriptions, what you say, and it becomes this general-purpose memory, and this means for organizing knowledge, which just expands the capacity of language in obvious ways. That's what you might expect.

It appears that the history was quite different. The first forms of writing were, you know, this guy owes this other person so much wheat, this person didn't pay their taxes. Bookkeeping is the kind of primordial form. And then quite a bit later, many hundreds of years later, people begin to pick up on those limitless possibilities.

Lead image: Ekaterina Gerasimchuk / Shutterstock

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

[ad_2]

Source link