[ad_1]

Explore

Fossils are like prehistoric puzzle pieces, helping us to reconstruct the distant past. Normally, such mineralized mementos take thousands of years to form, at the very least—and only a fraction of living matter submits to the process. But these precious specimens, so valuable to science, can also be faked—and natural history museums around the world are increasingly finding such fakes in their collections.

Fortunately, we're also getting better at detecting counterfeits. Earlier this year, scientists figured out that an enigmatic 280-million-year-old fossilized lizard, discovered in the Italian alps almost a century ago, is an elaborate hoax. Thinking to have been one of the oldest fossil reptiles and one of few specimens in which soft tissues were preserved, the lizard's appearance had puzzled paleontologists for decades. But when scientists from Italy and Ireland re-analyzed it using ultraviolet photography, 3-D surface modeling, and scanning electron microscopy, they found it is actually just a carving covered in black paint.

He took great pains to make the “fossil” look authentic.

Fossil forgeries are partly driven by a thriving collector's market, says Gabriel-Philip Santos, the director of visitor engagement and education at the Alf Museum of Paleontology in Los Angeles, California. “Many collectors are incredibly versed in paleontology and work really hard to contribute to the field,” he says. But the abundant sums they are willing to spend on specimens make the market an attractive target for fraudsters—and the forgeries are very bad for science.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

Below, seven other notorious fossil forgeries, and how experts sniffed them out.

The “Piltdown fly”

In 1966, when famous German biologist Willi Hennig described (in an article. article that, coincidentally, was published on April Fool's Day) what appears to be a modern-day fly trapped in Baltic amber, it was taken as evidence that the common insect had survived relatively unchanged for 40 million years. It took nearly three decades before another scientist, Andrew Ross, re-examined the specimen and realized that while the Baltic amber was real, someone had actually split it, hollowed it out, inserted a fly they trapped in resin, and resealed the halves. Following this discovery, it received the unflattering nickname “Piltdown fly” as a reference to the infamous Piltdown man.

Piltdown man

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

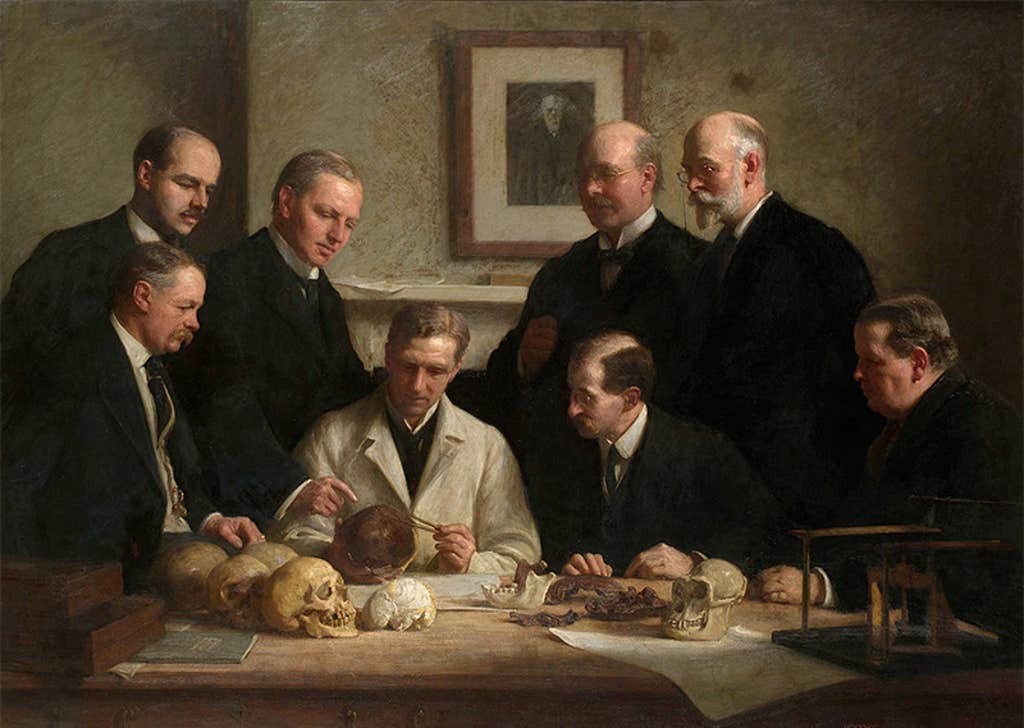

Arguably the most famous fossil fraud was Eoanthropus dawsonior “Dawson's dawn man.” After claiming in 1912 to find cranial fragments in a gravel deposit near Piltdown, in the United Kingdom, amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson reached out to fossil expert and museum curator Arthur Smith Woodward. Apparently convinced of the legitimacy of the find, Woodward joined Dawson in presenting before the Geological Society of London the “Piltdown man” as a Pleistocene-era “missing link” between primitive primates and modern-day humans. Although some raised questions about its legitimacy early on, the reception to the Piltdown man was largely positive at the time, as it reinforced a dominant and biased view of evolution: Many Western scientists believed the first humans evolved in Europe.

It wasn't until 41 years later, in 1953that three British scientists exposed it as a fake. By measuring how much fluorine the fossils had absorbed from the soil, the experts estimated how long they had been underground. Combined with careful physical inspection, they determined that the Piltdown remains were actually composites of much more recent human skull fragments and artificially colored primate teeth. Sadly, the damage had already been done: The Piltdown man led many experts to pursue accurate ideas about evolution, with close to 250 papers on the forged fossil published before the fraud was found out. Worse, it eroded the public's confidence in science. In 2016, an eight-year analysis named the hoax's most likely offender: Dawson himself.

Archaeoraptor

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

When experts announced the discovery of “Archaeoraptor liaoningensis” in 1999, the world paid attention: This supposedly extinct animal from China, whose fossilized remains suggested traits of both birds and dinosaurs, provided seemingly conclusive proof that birds descended from dinos. The details were published in National Geographic that year. But further scientific scrutiny revealed that this avian “missing link” was nothing more than a mashup of parts jammed together by cunning forgers. The parts were taken from a recently discovered Velociraptor relative, Microraptorand a Cretaceous-era fish-eater, Yanornis,among other as-of-yet unidentified animals. The deception did not permanently discredit the idea that birds sprang forth from dinosaurs, however, as numerous fossil finds in recent years have served as strong supporting evidence of this evolutionary connection.

The Calaveras skull

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

Not all fossil fakes are driven solely by the desire to make a quick buck; Sometimes, fraud finds are the work of petty pranksters. In 1866, California state geologist Josiah Whitney got his hands on a Pliocene-age skull that miners had reported unearthed in Calaveras County. Whitney, who saw this as proof of his staunch belief that humans walked the Earth alongside wooly mammoths, excitedly announced this find during a gathering of members of the California Academy of Sciences later that year. While Whitney did manage to convince some of his fellow academics, many doubted the skull's authenticity. Years later, an anonymous informant told a local newspaper that the miners had actually planted the skull—which a 1992 radiocarbon analysis placed at less than 1,000 years old—to trick Whitney, whose “very reserved demeanor” apparently irked them.

Johann Beringer's “Lying Stones”

In 1725, Johann Beringer, the dean of the University of Würzburg's Faculty of Medicine, developed an interest in acquiring strange rocks and specimens from beneath the earth—he called them “formed stones.” At the time, scholars knew little about how fossils were created. University librarian Johann Georg von Eckhart and professor J. Ignatz Roderich heard that Beringer had hired three teenagers to search for such artifacts for him. Seeing an opportunity to humiliate Beringer for what they considered a surplus of arrogance, they reported conspired with a local noble to carve impressions of fishes, frogs, insects, crabs, and land plants—even the sun and the stars—into pieces of limestone and plant them for Beringer's boys to collect. Over six months, his assistants dug up and sold him an estimated 2,000 such carvings. The doctor was duped, and even published a book about the finds a year later, with 21 engraved plates. When the deception was eventually discovered, an incensed Beringer sued von Eckhart and Roderick. In the end, the saga ended well for no one: The university cut ties with the offenders, and Beringer never published on fossils again.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

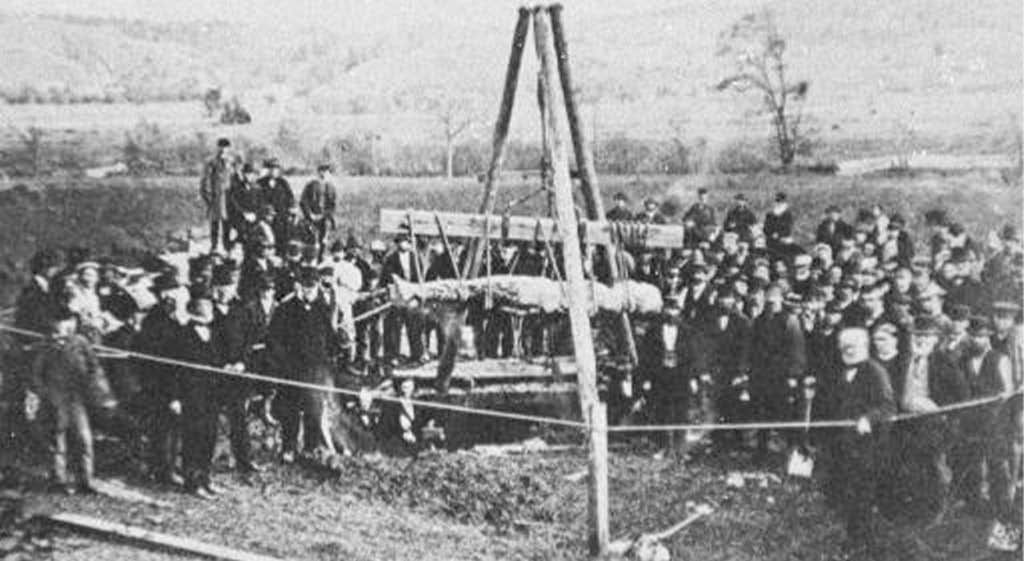

The Cardiff giant

How far would you go to prove a point? In 1868, tobacco dealer and science enthusiast George Hull decided that an elaborate hoax would be the best way to discredit a then popular Christian notion that giant humans once roamed the planet. He first paid for the creation of a 10-foot-tall gypsum statue based on his image. He took great pains to make the “fossil” look authentic, getting expert opinions and creatively altering the artifact's texture and colors using brute force and a cocktail of chemicals. Then, he buried it in his cousin's farm, where shocked workers discovered it the following year. Mere months later, after the giant had attracted considerable public attention, Hull revealed his secret and his motivation for doing so: to demonstrate just how gullible he thought the religious community was.

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

Humans walking beside dinosaurs

Modern science tells us that humans and dinosaurs missed each other by about 65 million years, but that hasn't stopped people from trying to find proof that our ancestors shared the planet with the dinos. And so, when people start finding ginormous elongated footprints Alongside dinosaur tracks in the Paluxy riverbed near the Glen Rose Formation in Texas, some creationists embrace it as evidence of a “young Earth.” In the years since, studies have suggested that instead of these tracks are, among other things, misidentified erosion marks, poorly preserved dinosaur footprints that only superficially resemble human tracks, and even manually carved fakes.

These stories of specimen skullduggery show easily we can be fooled by bad faith actors, a lack of scientific rigor, or both—a potent reminder that scientific discovery is always a work in progress.

Lead image: William Henry Holmes / Wikipedia Commons

ADVERTISEMENT

Nautilus Members enjoy an ad-free experience. Log in or Join now .

[ad_2]

Source link